Jan. 31, 2014

Updated Feb. 2, 2014 2:12 p.m.

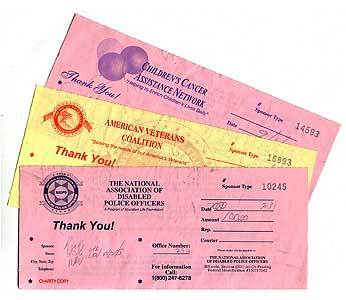

The phone rings. You hear a tragic tale about dying children or disabled firefighters or the devastation left by breast cancer. You reach for your credit card and make a donation, feeling like you've helped make the world a better place.

Sucker!

Commercial fundraisers – the for-profit companies behind the vast majority of those telemarketing appeals for charity donations – raised almost $300 million on behalf of nonprofits in California in 2012, according to figures collected by the state Attorney General.

The nonprofits got just a fraction of the booty – an average of only 37 percent, or $108 million -- and the commercial fundraisers kept the rest for themselves.

That's a steep dive from the year before, when nonprofits got more than half the take.

“These telemarketing companies are bottom-feeders,” said Doug White, a nonprofit consultant who teaches ethics and fundraising for Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. “It’s a ripoff. It’s a scam.

“If they were required to tell donors that the contract specifies that only 35 percent of gifts would actually go to the charity, the fundraising results would be terrible. But the Supreme Court has said they can’t be required to tell people that – it’s a matter of free speech and the First Amendment.

“I don’t blame the fundraisers,” White continued. “They’re for-profit companies doing their job. I blame the nonprofits that use them over and over and over again.”

BIG NAMES

Some of those nonprofits are big-name national charities you’ve surely heard of – Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the American Civil Liberties Union, Medecins San Frontieres USA, Oxfam, Save the Children, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, the U.S. Olympic Committee, the Natural Resources Defense Council – and those campaigns often wound up costing the charities money, rather than raising a single dime.

• One campaign for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in New York had revenues of $2 million – but the nonprofit wound up losing $1.8 million nonetheless, for a return of minus 92.8 percent, according to data collected by the California attorney general.

• One for Oxfam raised $210,859, but wound up costing the charity all that plus $178,050, for a return of minus 84.4 percent.

One for the Humane Society of the United States in Washington D.C. raised $1.6 million, of which only $139,768 went to the charity – a return of 8.9 percent. Several others were in negative territory.

• The U.S. Olympic Committee in Colorado Springs had a return of minus 77.2 percent on one campaign, and got just a fraction of the $2.6 million raised in its name in another campaign ($613,470, or a return of less than 24 percent).

• A campaign for Mothers Against Drunk Driving raised almost $4 million, but the charity saw only $516,015 of it, a return of 13 percent.

• That makes the campaign for Medecins San Frontieres USA seem almost flush: It raised more than $2 million, and the charity got $733,000 – a return of not quite 36 percent.

• And over the course of 10 campaigns, commercial fundraisers pulled in $8.2 million for the ACLU, and forwarded $3 million to the nonprofit – 36.5 percent of the take.

The Natural Resources Defense Council was in the red on all six of its campaigns. Save the Children was in the red on three out of four.

We asked these charitable organizations to weigh in; we’ll let you know if and when we hear back.

Many of the commercial fundraisers racking up dismal returns for charities – the CRF/Charitable Resource Foundation, DialAmerica Marketing, and many more -- work “care of” the Kansas City law firm Copilevitz & Canter LLC, and refer inquiries there.

We weren’t able to connect with Copilevitz & Canter by deadline, but Errol Copilevitz spoke to the Center for Investigative Reporting and Tampa Bay Times for a story that was headlined, “Meet the lawyer who keeps some of America's worst charities in business.”

Copilevitz has won landmark First Amendment cases that undercut government efforts to regulate sham charities and helped unleash an avalanche of junk mail and telemarketing calls on the American public, CIR/Tampa Bay reported. Thanks in part to Copilevitz, the government can’t limit how much charities spend on fundraising. And their for-profit solicitors don’t have to disclose how much they keep unless donors ask.

“There’s no doubt there are some people who start charities whose intentions aren’t the greatest,” he told CIR/Tampa Bay. “They’re looking to create a job for themselves, I suspect.”

But the choice is this, he said: Put up with groups that don’t do enough to help people in need, or stifle everyone, including the charity “that actually may come up with the cure to cancer.”

He doesn’t have much sympathy for people who give without realizing that little will reach the intended charities. “I think people understand that there’s a cost (to raising money),” he told CIR/Tampa Bay. “How long do you have to be telling them that?”

California’s Attorney General points out that most of the charities registered in California do not use commercial fundraisers. Historically, she said, such fundraisers return less than 50 percent of the contributions they raise to the charities they represent.

WHY?

So why on earth would a nonprofit use a commercial fundraiser when it gets such a small fraction of the take?

“The answer is easy,” said Larry Zucker, who once mounted major fundraising events as a senior associate vice president at California State University, Fullerton. “Say I’m a big name charity or have ‘firefighter’ in my name or something like that. If a commercial fundraiser can raise $1 million in my name and I can get 20 percent, well, that’s $200,000 I never otherwise would have had. That’s how they look at it.”

At Fullerton, Zucker knew he could never justify results like that to his community, so he never used telemarketers. But big nationals can get away with things that smaller nonprofits, more closely woven into the fabric of their communities, can not.

Zucker now runs a company called The Gavel Group in Lake Forest, which puts together auctions for nonprofits like the Orangewood Children’s Foundation, the Boys and Girls Club of Long Beach, the Palm Springs Charities Foundation, and dozens more. Even though The Gavel Group has never done a telemarketing campaign – “I despise telemarketers,” Zucker said – his company is technically a commercial fundraiser, and its results are reported beside the bottom-feeders in the attorney general’s annual report.

The Gavel Group makes the other commercial fundraisers look better by boosting the state average. It returns 72.5 percent of what it raises to clients – almost double the state average. Zucker’s group puts together those packages you see auctioned off at charity fundraisers – luxury box tickets to a Dodgers game, say, along with a night in a swanky hotel – and does everything from displaying to auctioneering to cashiering. Gavel did 54 charity auctions last year.

There are others that return the overwhelming majority of donations to charity – Coinstar and Deals for Good among them.

HANG UP

Zucker does not donate to telemarketers.

“I just don’t give over the phone,” he said. “If I want to donate to a nonprofit, I give directly.”

And that’s the best advice anyone can offer on the subject. If you want to give to a charity that moves your heart – Oxfam, the ACLU, MADD, whatever – look it up online and donate directly. Hang up when the telemarketer calls -- or, if you want to have a little fun, ask how much of your donation will actually go to the charity before you hang up. They’re supposed to respond truthfully, and the answer may shock you.

Another bit of wisdom: Beware of charities with the words ‘police’ and ‘firefighter’ and ‘veteran’ and ‘cancer’ in their names. There are many worthy ones, but many snakes as well. Please, check out a charity before you give. We like nonprofit watchdog sites like charitynavigator.org and guidestar.org.

White, who teaches at Columbia, said that the New York state attorney general compiles similar data on commercial fundraisers there – and 38.5 percent went to charities, according to the Empire State’s most recent report. Nearly identical to Callifornia’s 37 percent. In New York, it amounted to $92.7 million of the $240.5 million raised in charities’ names.

And that’s just not enough, White said.

“The larger truth is that these total dollars are being deducted on donors’ income taxes even though only a small percentage is going toward the charity’s cause, so it’s essentially being paid for by the rest of us,” White said. “That’s an outrage. You can understand an unestablished charity using professional fundraisers to help it get started, but for it to go on, chronically, forever – that’s an outrage. That’s terrible. If there was a black and white choice, I’d say nonprofits shouldn’t be allowed to do it, or should be reprimanded every time they do.”

New York’s attorney general works up a good head of steam over the issue, too. “Overall far too much money is spent on telemarketers’ fees and expenses, and far too little on charity,” says New York’s “Pennies for Charity” report. “As telemarketing continues to be widely used by charities, greater efforts are needed to reduce amounts paid to professional fundraisers and increase amounts going to charity. It is imperative that charities negotiate the best deals possible for their organizations.

“We urge charities to heed the advice contained in this report…and say no to bad fundraising deals. Board members should ask themselves: Why are we allowing such a high percentage of our donations to be paid to a for-profit professional fundraising company? Is that really the best we can do?”

Contact the writer: [email protected]

Cracking down on bad charities

We’ve been telling you about bad charities that spend the overwhelming majority of their money on raising money, rather than on good works.

And we’ve been telling you how the states of Oregon and Florida are trying to rein in bad charities by punishing nonprofits that spend too little on their core missions, and too much on fundraising and management.

We at the Watchdog have adopted this as our crusade for 2014, and are pleased to report that Assemblyman Travis Allen (R-Huntington Beach) is busily working on legislation in Sacramento that would bring The Oregon Idea to California – i.e., set a barebones minimum on how much nonprofits must actually spend on good works in order to be recognized as nonprofits by the state government – and given the tax breaks thereof.

It may be as simple as saying that half of all proceeds have to be used for charitable purposes, said Joe Kerr, president of the Orange County Professional Firefighters Association. (Tired of being confused with all those bogus firefighter charities, it is working with Allen’s office.)

Allen and his staffers have met with folks from the California Association of Nonprofits – which didn’t much like the idea when we floated it by them – “to begin the dialogue to craft language that will avoid any unintentional consequences to non-profits in his efforts to protect the integrity of the charities and the good-natured donors throughout California,” said Ryan Q. Hanretty, Allen’s capitol director, by email.

The bill must be introduced by Feb. 22 to be considered in this legislative session.

Source: The Orange County Register

Updated Feb. 2, 2014 2:12 p.m.

The phone rings. You hear a tragic tale about dying children or disabled firefighters or the devastation left by breast cancer. You reach for your credit card and make a donation, feeling like you've helped make the world a better place.

Sucker!

Commercial fundraisers – the for-profit companies behind the vast majority of those telemarketing appeals for charity donations – raised almost $300 million on behalf of nonprofits in California in 2012, according to figures collected by the state Attorney General.

The nonprofits got just a fraction of the booty – an average of only 37 percent, or $108 million -- and the commercial fundraisers kept the rest for themselves.

That's a steep dive from the year before, when nonprofits got more than half the take.

“These telemarketing companies are bottom-feeders,” said Doug White, a nonprofit consultant who teaches ethics and fundraising for Columbia University's Master of Science in Fundraising Management program. “It’s a ripoff. It’s a scam.

“If they were required to tell donors that the contract specifies that only 35 percent of gifts would actually go to the charity, the fundraising results would be terrible. But the Supreme Court has said they can’t be required to tell people that – it’s a matter of free speech and the First Amendment.

“I don’t blame the fundraisers,” White continued. “They’re for-profit companies doing their job. I blame the nonprofits that use them over and over and over again.”

BIG NAMES

Some of those nonprofits are big-name national charities you’ve surely heard of – Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the American Civil Liberties Union, Medecins San Frontieres USA, Oxfam, Save the Children, Planned Parenthood Federation of America, the U.S. Olympic Committee, the Natural Resources Defense Council – and those campaigns often wound up costing the charities money, rather than raising a single dime.

• One campaign for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in New York had revenues of $2 million – but the nonprofit wound up losing $1.8 million nonetheless, for a return of minus 92.8 percent, according to data collected by the California attorney general.

• One for Oxfam raised $210,859, but wound up costing the charity all that plus $178,050, for a return of minus 84.4 percent.

One for the Humane Society of the United States in Washington D.C. raised $1.6 million, of which only $139,768 went to the charity – a return of 8.9 percent. Several others were in negative territory.

• The U.S. Olympic Committee in Colorado Springs had a return of minus 77.2 percent on one campaign, and got just a fraction of the $2.6 million raised in its name in another campaign ($613,470, or a return of less than 24 percent).

• A campaign for Mothers Against Drunk Driving raised almost $4 million, but the charity saw only $516,015 of it, a return of 13 percent.

• That makes the campaign for Medecins San Frontieres USA seem almost flush: It raised more than $2 million, and the charity got $733,000 – a return of not quite 36 percent.

• And over the course of 10 campaigns, commercial fundraisers pulled in $8.2 million for the ACLU, and forwarded $3 million to the nonprofit – 36.5 percent of the take.

The Natural Resources Defense Council was in the red on all six of its campaigns. Save the Children was in the red on three out of four.

We asked these charitable organizations to weigh in; we’ll let you know if and when we hear back.

Many of the commercial fundraisers racking up dismal returns for charities – the CRF/Charitable Resource Foundation, DialAmerica Marketing, and many more -- work “care of” the Kansas City law firm Copilevitz & Canter LLC, and refer inquiries there.

We weren’t able to connect with Copilevitz & Canter by deadline, but Errol Copilevitz spoke to the Center for Investigative Reporting and Tampa Bay Times for a story that was headlined, “Meet the lawyer who keeps some of America's worst charities in business.”

Copilevitz has won landmark First Amendment cases that undercut government efforts to regulate sham charities and helped unleash an avalanche of junk mail and telemarketing calls on the American public, CIR/Tampa Bay reported. Thanks in part to Copilevitz, the government can’t limit how much charities spend on fundraising. And their for-profit solicitors don’t have to disclose how much they keep unless donors ask.

“There’s no doubt there are some people who start charities whose intentions aren’t the greatest,” he told CIR/Tampa Bay. “They’re looking to create a job for themselves, I suspect.”

But the choice is this, he said: Put up with groups that don’t do enough to help people in need, or stifle everyone, including the charity “that actually may come up with the cure to cancer.”

He doesn’t have much sympathy for people who give without realizing that little will reach the intended charities. “I think people understand that there’s a cost (to raising money),” he told CIR/Tampa Bay. “How long do you have to be telling them that?”

California’s Attorney General points out that most of the charities registered in California do not use commercial fundraisers. Historically, she said, such fundraisers return less than 50 percent of the contributions they raise to the charities they represent.

WHY?

So why on earth would a nonprofit use a commercial fundraiser when it gets such a small fraction of the take?

“The answer is easy,” said Larry Zucker, who once mounted major fundraising events as a senior associate vice president at California State University, Fullerton. “Say I’m a big name charity or have ‘firefighter’ in my name or something like that. If a commercial fundraiser can raise $1 million in my name and I can get 20 percent, well, that’s $200,000 I never otherwise would have had. That’s how they look at it.”

At Fullerton, Zucker knew he could never justify results like that to his community, so he never used telemarketers. But big nationals can get away with things that smaller nonprofits, more closely woven into the fabric of their communities, can not.

Zucker now runs a company called The Gavel Group in Lake Forest, which puts together auctions for nonprofits like the Orangewood Children’s Foundation, the Boys and Girls Club of Long Beach, the Palm Springs Charities Foundation, and dozens more. Even though The Gavel Group has never done a telemarketing campaign – “I despise telemarketers,” Zucker said – his company is technically a commercial fundraiser, and its results are reported beside the bottom-feeders in the attorney general’s annual report.

The Gavel Group makes the other commercial fundraisers look better by boosting the state average. It returns 72.5 percent of what it raises to clients – almost double the state average. Zucker’s group puts together those packages you see auctioned off at charity fundraisers – luxury box tickets to a Dodgers game, say, along with a night in a swanky hotel – and does everything from displaying to auctioneering to cashiering. Gavel did 54 charity auctions last year.

There are others that return the overwhelming majority of donations to charity – Coinstar and Deals for Good among them.

HANG UP

Zucker does not donate to telemarketers.

“I just don’t give over the phone,” he said. “If I want to donate to a nonprofit, I give directly.”

And that’s the best advice anyone can offer on the subject. If you want to give to a charity that moves your heart – Oxfam, the ACLU, MADD, whatever – look it up online and donate directly. Hang up when the telemarketer calls -- or, if you want to have a little fun, ask how much of your donation will actually go to the charity before you hang up. They’re supposed to respond truthfully, and the answer may shock you.

Another bit of wisdom: Beware of charities with the words ‘police’ and ‘firefighter’ and ‘veteran’ and ‘cancer’ in their names. There are many worthy ones, but many snakes as well. Please, check out a charity before you give. We like nonprofit watchdog sites like charitynavigator.org and guidestar.org.

White, who teaches at Columbia, said that the New York state attorney general compiles similar data on commercial fundraisers there – and 38.5 percent went to charities, according to the Empire State’s most recent report. Nearly identical to Callifornia’s 37 percent. In New York, it amounted to $92.7 million of the $240.5 million raised in charities’ names.

And that’s just not enough, White said.

“The larger truth is that these total dollars are being deducted on donors’ income taxes even though only a small percentage is going toward the charity’s cause, so it’s essentially being paid for by the rest of us,” White said. “That’s an outrage. You can understand an unestablished charity using professional fundraisers to help it get started, but for it to go on, chronically, forever – that’s an outrage. That’s terrible. If there was a black and white choice, I’d say nonprofits shouldn’t be allowed to do it, or should be reprimanded every time they do.”

New York’s attorney general works up a good head of steam over the issue, too. “Overall far too much money is spent on telemarketers’ fees and expenses, and far too little on charity,” says New York’s “Pennies for Charity” report. “As telemarketing continues to be widely used by charities, greater efforts are needed to reduce amounts paid to professional fundraisers and increase amounts going to charity. It is imperative that charities negotiate the best deals possible for their organizations.

“We urge charities to heed the advice contained in this report…and say no to bad fundraising deals. Board members should ask themselves: Why are we allowing such a high percentage of our donations to be paid to a for-profit professional fundraising company? Is that really the best we can do?”

Contact the writer: [email protected]

Cracking down on bad charities

We’ve been telling you about bad charities that spend the overwhelming majority of their money on raising money, rather than on good works.

And we’ve been telling you how the states of Oregon and Florida are trying to rein in bad charities by punishing nonprofits that spend too little on their core missions, and too much on fundraising and management.

We at the Watchdog have adopted this as our crusade for 2014, and are pleased to report that Assemblyman Travis Allen (R-Huntington Beach) is busily working on legislation in Sacramento that would bring The Oregon Idea to California – i.e., set a barebones minimum on how much nonprofits must actually spend on good works in order to be recognized as nonprofits by the state government – and given the tax breaks thereof.

It may be as simple as saying that half of all proceeds have to be used for charitable purposes, said Joe Kerr, president of the Orange County Professional Firefighters Association. (Tired of being confused with all those bogus firefighter charities, it is working with Allen’s office.)

Allen and his staffers have met with folks from the California Association of Nonprofits – which didn’t much like the idea when we floated it by them – “to begin the dialogue to craft language that will avoid any unintentional consequences to non-profits in his efforts to protect the integrity of the charities and the good-natured donors throughout California,” said Ryan Q. Hanretty, Allen’s capitol director, by email.

The bill must be introduced by Feb. 22 to be considered in this legislative session.

Source: The Orange County Register